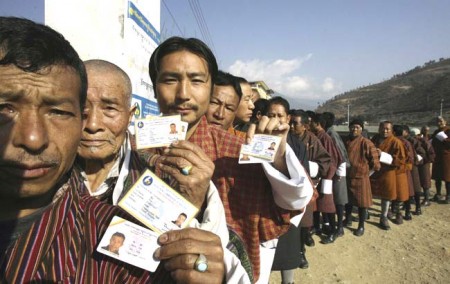

Bhutan’s democracy in action

2008 – that is the year when Bhutan claimed to have sown the seed of democracy. Despite allegations that thousands of citizens were barred from exercising their right to vote, the small Himalayan kingdom was making all progress to open up quite widely as it prepared for the second parliamentary elections early next year.

If things worked well democratically, this small nation with less than 350,000 voters will get at least six parties contesting in the second parliamentary election, against two in 2008.

Very recently, at least four new parties have come forward expressing interest to contest in the next election.

Due to law conditions that a party should have candidates to contest in all 47 constituencies to be eligible to register as legal entity, the new parties, or rather call them interest groups at this stage, are facing a hard time finding capable candidates. Finding individuals holding at least a bachelor degree and having an interest in politics in such a small society is terribly difficult.

Many Bhutanese, who lived most part of their lives in a closed society, are less interested in open politics, thus making the set to draw candidates further smaller. Fresh graduates entering job market are the only bunch from where all parties must find their suitable candidates..

According to Bhutan Today, one of the new parties in making Druk Nyamrup Tshogpa (DNT) has got hold of 31 candidates by the second week of July. Kuensel, the government run newspaper, said Bhutan Kuen-nyam Party has so far found 17 candidates. Druk Chirwang Tshogpa (DCT) and Druk Mitser Tshogpa (DMT) have kept mum of their progresses.

All parties will be filtered through a primary round to choose only two for the final round of election. Constitutionally, only two parties are represented in the parliament.

Even the incumbent opposition People’s Democratic Party (PDP) is finding it hard to field its previous candidates for next election. After winning only 2 out of 47 seats in the lower house National Assembly (upper house National Council is apolitical) in 2008 election, most of its candidates have left the party for personal business or have joined the new parties in making.

Additionally, the party is yet to clear its debt incurred during 2008 election, without which the Election Commission will not allow it to contest the election.

The ruling party Druk Phuensum Tshogpa (DPT), is the only party with the confidence to run the next election. Having 45 MPs in current list, the party has to see for two candidates to meet the election criteria. It has cleared the debts incurred during the 2008 election, after the party made it mandatory for its MPs and ministers to contribute Nu 200,000 (approx. AU$3,650) each.

DPT and PDP had each incurred over Nu 20 million (approx. AU$370,000) debt when they invested in their last election campaigns, and for almost four years, the parties failed to clear it. The government-run newspaper Kuensel termed it as a “debt-ridden” democracy.

The loan repayment took such a long time because the only source of income for the party is members’ donations. Not many went on to become party members and not all party members were able to contribute big amounts.

The new parties says they will complete all formalities of finalising party charter, manifesto and identifying candidates in the next few months to prepare for the next election.

The election will certainly be a difficult choice for the people. Except one , (DCT has said it follows Democratic Socialism), none of the other parties have stated their political philosophy. There are no big agendas for parties to woo the voters. Gross National Happiness (GNH) is the only item for the parties to talk to voters. . DMT has vaguely said its primary agenda will be youth unemployment, not GNH.

The parties have not been able to pick up some of the thorny issues such as stripping off the citizenships of thousands of southern Bhutanese in 1990, the political suppression in eastern Bhutan and the future of fatherless children in central Bhutan.

The first two issues, if injected into debates, would make huge influence in the way people vote. Few DPT MPs have recently made unsuccessful attempts to bring the issue into discussion.

It remains to see if the second parliamentary election will liberate the closed Bhutanese society and bring democracy into action.

Published in Our World Today