Bhutan Elections 2.0: A Critical Appraisal

Once stunt dissenter of democratic governance, Bhutan gradually heeds to it. The Son King, educated in democratic environment, is taking lead to establish the system firmly in his reign. But it remains to see if he will abide by his sincere efforts all through his life.

Background

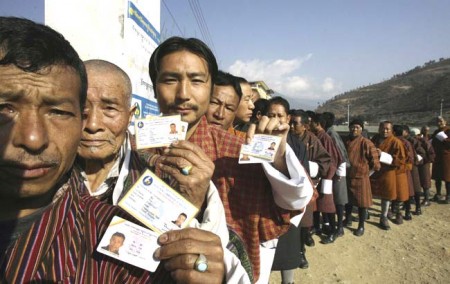

Bhutan, one of the youngest democracies in the world, is struggling to stabilise its government and political system. Nationwide elections for National Assembly and National Council – only the second in the country’s history – are expected to be held in the next few months. National Council elections are expected by April and National Assembly by June/July. There is not much talk about the probable election of apolitical National Council. It is the National Assembly, because of its nature, that remains at the centre of political discourses and debates. The elections, second in the series, are not merely electing parties to the parliament but for parties to face myrid of challenges in stabilising the system. They are struggling to operate freely under electoral laws which, while claiming to ensure fairness, stifle inclusive democracy and make it difficult to participate at all.

In order to better understand these pressures, it is necessary to look back over the short history of democracy in Bhutan. In December 2006, King Jigme Singye announced he would abdicate, making way for the young crown prince, King Jigme Khesar Namgyal Wangchuk. This move heralded a new era for Bhutan – the establishment of substantive democracy – under the guidance of its new and popular monarch.

Shortly after his enthronement, King Khesar, often referred to as K5 (he is the fifth King of Bhutan) by his citizens, made clear his desire to see great changes in the country’s political system. Political parties, once regarded as a wholesale threat to peace and stability, came into existence. Bhutan’s first general election, held in 2008, paved the way for the Bhutanese people to experience the world’s most popular form of government. Of the two parties in the field, Druk Phunsum Tshogpa (DPT) won 45 of 47 seats in the lower house, making the People’s Democratic Party (PDP) the world’s smallest opposition. Bhutan’s upper house, meanwhile, is not elected. Additionally, the constitution promulgated in July 2008 formally changed the absolute monarchy in Bhutan to a constitutional one.

Voice for change

The uprising in 1990 and 1997-98 was certainly a demand for a political change. Partly influenced by the political changes sweeping across the region, Bhutanese in southern districts saw the need for making king as constitutional head while delegating other powers to the elected representatives of the people.

There were heaps of similar demands put forward by a number of groups – including political parties and human rights groups that came up in exile. The Bhutan People’s Party (BPP), first to put such demands, resolved that Bhutan needs a constitutional monarch and multi-party political system. Other groups made demands on similar lines.

The government had, then, responded retrospectively. Those calling for changes were branded anti-nationals and terrorists and their activities as treason against king, country and people. Almost 18 years later, King Jigme Singye, who then opposed presence of political parties in the country, felt the need of such system. In one of his interviews with Indian journalist, King Wanghuck had mentioned he would abdicate his throne in favour of crown prince if he failed to resolve the southern Bhutan problem. He stood to his words to abdicate finally. Many feel resettlement of Bhutanese refugees to western countries has resolved the southern Bhutan problem. It has not.

The Bhutan royal family felt the needs for more political changes seeing the discontent rising from eastern district as well under the leadership of Rongthong Kunley Dorji in 1997-98. Had there been no expulsion of Dorji, formation of Druk National Congress (DNC) and eastern uprising, political changes in Bhutan would have been slower though certain.

The biggest democracy in the world and the largest donor, India played a negative role in flourishing democratic culture in Bhutan. In Nepal’s case, India extended support for the pro-democratic forces while in Bhutan it didn’t. The fair reason could be the position maintained by the monarchs. Bhutanese monarch remained ever loyal to India while Nepalese monarch made efforts to remain equidistant to India and China. All efforts Bhutanese refugees made failed at the cost of India, not Bhutan.

No matter what factors stimulated for political changes in Bhutan, it has finally started. The first election was like rehearsal for people. Not all voters have understood the need for political change, democratic rights and importance people’s representatives being operators of the state machineries.

While overall voter turnout in first general election was much higher than expected, the election failed to address the prevailing grievances of the people, and was not as democratic as expected. There were reports of many eligible voters being denied the right to cast their ballots.

Election observation

There were many complaints about the poll results in 2008 and about local government elections held thereafter. The two elected members of the PDP had initially tendered their resignations after allegations of forgery. Their claim was the wee hour silent campaigning by the government employees who were more loyal to Jigmi Thinley. Civil servants were the most influential people in Bhutanese society until then but it remains to greater investigation before we accept opposition claims.

It was partially related to issue of election monitoring. Election monitoring was poor in 2008, with only a few individuals handpicked by Thimphu acting as observers. Monitoring mechanisms were almost completely absent during local government elections.

There are no guarantees that these conditions will improve during elections likely to be held in three rounds in April and June/July 2013. Neither the government nor the Election Commission has disclosed whether or not international observers will be invited for monitoring this time. As a close follower of the Indian electoral system and being trained in India, Bhutan is unlikely to allow international observers to monitor how elections are conducted. The credibility of the election will depend on the implementation of internal monitoring mechanisms, which could and should be aided by international observers, both in monitoring and providing valuable feedback.

Candidates

Many Bhutanese, having lived for so long in a closed society, are not convinced of the importance of politics. Initial media reports claim people were not happy with the political changes taking place in the country. The psychological waves it made negative impact in finding right candidates for the election.

Very few are interested in joining political parties, making the pool from which parties can draw candidates even smaller. Recent graduates, who represent the largest demographic group of eligible candidates, are discouraged by the stringent rules of Bhutan’s two-party parliament, as well as the difficulties they may face in re-entering the job market if unsuccessful in politics. They have quietly observed the fate of PDP candidates who failed to be elected in 2008. It was hard time for these unsuccessful candidates to re-enter into the job market.

With these and other restrictions in place, even the incumbent opposition is finding it hard to field candidates for the next election. After winning only two out of 47 seats in the National Assembly in the 2008 election, most of the PDP’s candidates left the party to pursue personal businesses and career, or have joined other parties or interest groups. As of December, the party had 39 candidates ready for the next election, only 15 of whom are re-contesting. Repeated but failed efforts to bring back the founding president Sangye Ngedup caused friction in PDP leaving many out of the foray.

The DPT have confirmed the change of one candidate, while the futures of Speaker Jigmi Tshultim and Home Minister Minjur Dorji have become uncertain after the Anti-Corruption Commission filed criminal cases against them in Mongar District Court in November. Trial of the case has begun in early December. They are charged of illegally allotting government lands to their relatives some years back.

Stable government is the sole objective behind letting only two parties be represented in the parliament. The idea behind two-party parliament might have emerged out of the political cloud in South Asia where parliament and government remained unstable due to multiple parties represented. The constitution is so strict in giving a stable government that once elected the MPs are not allowed to change their party until they finish their term. With two parties represented, the parliament remains stable, but it falls far short of representing the diverse range of political opinions held in Bhutan.

Unless the disparate voices of differing political opinion are given a platform from which to be heard – both during and after the electoral campaigns – a cohesive, vibrant and inclusive government remains a distant dream. This is dictated democracy.

Rules of the game

Of the three applications submitted by fledgling parties eager to take part in the 2008 elections, the Election Commission of Bhutan accepted only two. Today, new parties have emerged with high hopes for inclusion, even though they lack the requisite number of candidates. Two of them have received registration with the commission. The third one is waiting the response from the commission. Suggestions even appeared for merger of these new parties to form a bigger and better, but differences in political opinions and thoughts will certainly keep them apart. Increasingly, parties and political operatives are questioning the Election Commission’s stipulation that parties must have 47 candidates – one for each constituency – in order to run in the primary round. However the commission has provided the option for candidates from parties unsuccessful in the primaries to join one of the two parties vying for majority in the National Assembly in the final round.

The presence of more parties in the field will make little difference in the way the Bhutanese parliament and government work, because the constitution dictates that only two parties are permitted to sit in parliament. Other parties will be filtered through the primary round, thus stripping them from pursuing their political goals. The stringent requirements for participating in primary elections, combined with this exclusionary endgame, serve to strongly discourage new political parties from entering the formal political process. Practically, only two parties will have role in Bhutanese democracy. Those eliminated in primary round will eventually die in next five years’ time in absence of political activism. It is bi-party system, not a multi-party democracy.

The legal prescription that candidates must have a bachelor’s degree (or equivalent qualifications) is particularly disheartening for an older generation of Bhutanese who, by and large, lacked access to higher education. Silent discontent of this generation is against being ruled by a young bunch. By norms of Bhutanese culture, only seniors can be the dominating figure. Young people, while more qualified, are often reluctant to embark on political careers, largely because of the restrictions described above.

There are other restriction in place for another large section of people who could be interested in political discourses and career. Charges of acting against the state or the royal family, or evidence of support for or participation in the pro-democratic movements in 1990 and 1997-8, are all impediments for anyone wishing to pursue a career in politics. Many political leaders arrested for demanding political change in those years remain in jail to this day. Druk National Congress in 2009 had published the names of 15 inmates arrested from 1997-98 demonstrations. It still remains unknown who many of those arrested in 1990 are in jail now. Relatives of these leaders, and also refugees currently in Nepal or resettled in Western countries, have not yet received security clearance from the government, preventing them from participating either as voters or candidates. There are few hopes in Thimphu or beyond that these restrictions will either be eased or lifted in time for this year’s elections, raising serious concerns over whether Bhutan has truly embraced democracy.

Bhutan is waiting for game changers who can bring twist here. With more political parties coming forward, there is bigger realm in politics for the game changers to join the race. Despite the difficulties the Election Commission has created for new political parties to enter into the game, four new political groups had originally expressed interest in participating in this year’s election. At the time of writing this report, the state-owned Bhutan Broadcasting Service reported that a new party – Druk Nyamrup Tshogpa (DNT), literally translated as the Druk Democratic Socialist Party – had found 33 eligible candidates to run in the election. Meanwhile, Kuensel, the government-run newspaper, said the Bhutan Kuen-nyam Party (BKP) has a total of 29 candidates, although only a few of these have been publicly named so far. Another party, the Druk Chirwang Tshogpa (DCT), has 45 confirmed candidates. A fourth party calling itself the Druk Mitser Tshogpa failed to gather enough candidates, and so announced that it would transform itself into a ‘political youth group’ of PDP. Of DNT, BKP and DCT who applied for registration, first two have received certificate of registration as political party.

Media and democracy

Questions have been raised if the budding media industry is serving to its fullest for the advancement of democracy. Most of the time, mainstream politics, government activities and NGO programmes dominate media contents.

One of many reasons behind media failure to cover wider issues is the government intervention. The government is coercing media not to act against government. Kuensel has changed its traditional role of being mouthpiece of the government to being promoter of both government and the ruling party. The ‘public ad’ regime imposed by the government has fundamentally forced media to remain loyal to the government or else shut. Media find it hard to survive without government advertisements. The government is taking this advantage to control how media should work. A circulation by Communication Ministry early this year (leaked only a few months ago) against providing any advertisement to ‘The Bhutanese’ bi-weekly is a solid manifestation of the government’s non-tolerance policy on criticism. Other private newspaper fear similar repercussion for any critical news against government.

Ideology and agenda

Communication secretary Kinley Dorji, who worked for years as editor of Kuensel, in several interviews to media had mentioned the necessity of Bhutanese media making Gross National Happiness (GNH) as priority area of reporting. It appears the government is prescribing GNH as the only substance of news. In fact, GNH is the only ideology (in essence GNH is development philosophy while parties turned it into a political ideology) for all parties, except one. The preachers of GNH and the regime invest all their energy to make GNH as the ultimate basis of governance in Bhutan. When United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) accepted Bhutanese proposal to conduct more research on happiness to develop it as one of the human development indices, it prompted the Bhutanese preachers to assume that GNH is the only ideology Bhutanese political parties should have and promote. With only few years for general people having access to TV and Internet, Bhutanese society is yet to accept the need of political ideology other than GNH. Until we see greater political consciousness in people, GNH will rule the Bhutanese political landscape.

And political ideology is unlikely to become determining factor for parties to win the election. The Bhutanese suffrage has no or little knowledge of long-term goals of any political ideology. On the other hand, educated voters have seen the regional politics where parties have not worked to effectuation of their ideology. This has triggered psychological impact on Bhutanese voters that mere conventional political ideology cannot form the basis to choose pro-citizen leaders. Instead, royal blessing, GNH (claimed to be formulated by 4th monarch) and bureaucracy determine the outcome of the result.

Democracy education

Democracy education is very poor. The constitution and the laws restrict political parties to reach out to people and talk on democratic process, elections and voting rights and obligations except during election campaigns. The government is not keen to invest on democracy education. In fact the government never allocated budget for this in last five years. UN system based in Thimphu and few INGOs through their partners in the country made little efforts within the capital city to conduct sessions on voting, adult franchise, political parties, their role, role of other arms of the state in democracy.

For a sustainable and stable democratic system, Bhutan needs to invest heavily on public consciousness on democratic rights and responsibilities. The political parties must constantly interact with the people round the year, not just during the election period. Examples from across the globe has taught us that more the political parties reach out to the people and interact with them about their daily needs and involve them in the national development dialogue, stronger will be the democracy. Such people-friendly party will win the hearts of the voters.

Voter education is important in emerging democracy like Bhutan. The voters should have the idea on weighing how parties are faring with the promises they made. And which parties have appropriate agenda to address their needs. Until voters are conscious enough to decide his/her vote based on agenda and idea, it is the social domination of a candidate that decides which party wins.

The frequency of interaction between parties and the people will, to some extent, influence voters in their choices in 2013. While most political discourse concentrates on the capital city, it remains to be seen how the new political groups will remain close to voters and interact with them. After the 2008 elections, parties have drawn criticism for failing to reach and interact with voters.

Party finance

One reason for this was the debilitating financial situation of the existing parties. Sources of income for political parties are almost non-existent. The government provides funding for election campaigns only; at all other times, parties have to survive on membership fees and individual volunteer donations of up to BTN 500,000 (approximately USD 9100). International financial support is banned. Both parties in the current parliament incurred a debt of over BTN 20 million (approximately USD 364,500) each in the previous elections, and only completed their repayments very recently. The Election Commission had warned that parties with debt would be disqualified from contesting the 2013 election.

In October, the national gathering of central committee members and district co-ordinators of the DPT proposed a monthly salary of BTN 5000 (USD 91) for district co-ordinators and BTN 4000 for constituency co-ordinators, with staff at lower levels being paid on an ever-decreasing sliding scale thereafter. Calculating for 20 districts, 47 constituencies, 206 gewogs (groups of villages) and 1044 villages, the DPT alone would require around BTN 3 million (about USD 54,500) every month. Considering its present levels of income and membership, and taking into account the legal provisions banning foreign donations, the DPT will be unable to meet these expenses in the near future.

The parliamentarians for last five years exchanged hard words on whether the state should fund political parties. The ruling party proposed that state must financially support two parties in the parliament. The opposition and the National Council opposed the idea saying it is unconstitutional. Though it is not the business of the Election Commission, it strongly opposed the proposal. However, the constitution does not speak whether the state funding for political parties is allowed. Allegations are that DPT tried to influence election by use of money. Had the DPT proposal been approved by the parliament, it could have discouraged new political aspirants to enter into political fray. But could have given financial security for the existing parties to work towards strengthening democracy. The newly registered parties are yet to speak what their stand is on the proposal.

Election issues

The Bhutanese electorate is something of a mixed bag. The dynamics of voters’ demography is changing swiftly. Young population is exceeding that of old ones. The politically-conscious youth vote is likely to be the deciding factor in this election. Young people, perhaps psychologically buoyed by the king’s own age (Khesar is currently 32), have begun to desire younger elected leadership too. According to Home Ministry documents, in 2013 Bhutan will have 112,600 young voters – defined as those between the ages of 18 and 25 – of whom 70,000 will be exercising their voting rights for the first time. The youth vote will make up 30 percent of the electorate, but that does not guarantee that the issues pertinent to this bloc will be addressed. People behind DMT, which set youth issue as its primary agenda, failed to turn the group into a political party. Other parties register the issue as secondary. The Bhutanese government’s bigwigs, who earned their fortunes working under the direct rule of the king, still dominate national politics. And these bigwigs had never embraced the idea and issues of youths into their list of agenda.

Other factors will also affect the result: the contentious issue the ethnic cleansing carried out in the southern districts in the 1990s, the political suppression of the eastern districts in 1997-98, and the discontent felt by the stateless young population in the central districts. The call for greater reforms in 1990, and the subsequent expulsion of those demanding change, has resulted in a growing number of Bhutanese taking refuge abroad in the US, Australia, Canada and Western Europe.

The first elected government announced that Bhutan would take back ‘eligible’ citizens unwilling to be resettled abroad. The current government appears to believe that repatriating a small number of those currently displaced to refugee camps in Nepal could help dilute the discontent in southern Bhutan. The opposition party objected to the government’s plans for repatriation, arguing that this might open the doors to ‘terrorists’. New political parties have remained silent on the issue: demands for equality by the eastern Bhutanese and the issue of stateless children have never been priorities for Bhutanese political parties and authorities.

Indeed, parties and candidates have maintained self-censorship on a variety of issues. The two registered parties in 2008 made only piecemeal efforts to speak on the refugee problem, but even this was merely to win the votes of those affected. With over 75,000 refugees resettled internationally already, the issue may not be powerful enough to produce southern sympathy this time around. However, the 80,000 ‘ineligible voters’ in the south and east will be an attractive source of future votes. The politically sensitive issue of citizenship rights will likely receive less attention. In a patriarchal society such as Bhutan, issues like this will continue to be suppressed.

Gender and politics

Today, the National Assembly has four female members, while the upper house has six, meaning women account for less than 14 percent of parliament. Unfortunately, debates surrounding female empowerment do not appeal to the electorate. Women empowerment is not captivating affair for political leadership. However, NGOs are encouraging women to join politics through advocacy programmes. S B Ghalley – who intends to run for election with the DCT – says his party ensures equality for all members, without giving priority to women. PM Thinley said, they believe in meritocracy not on reservation. Two of the new political parties made headlines earlier this year when they flirted with the possibility of nominating female party leaders. One has, in fact, now done so: Lily Wangchuk, a former UN employee, now leads the DCT. But the appointment of female party leaders will not change the overall climate for women in politics. Female participation will have little impact on national politics unless women’s roles in family life, society and the workplace also change. There is no easy road for women to show their presence in politics and demonstrate their value.

Today, National Assembly (47 seats) has 4 women and National Council (25 seats) 6 women members. In short, women’s presence is less than 14 per cent in national parliament and five per cent in local governance including one gup (village headman), according to Bhutan Observer weekly.

In the eyes of NGOs and activists, women are the sole marginalised group in terms of political participation. These organisations have ignored the plight of ethnic minorities entirely, and this approach is further compounded by the absence of a governmental effort to identify, count and include these groups in the nation-building process. This apathy invites complications and difficulties in determining the futures of marginalised people. Without statistical data, it is impossible to assess Bhutan’s commitment to equal opportunities, as well as to test whether government and INGO initiatives have made a substantial difference to the lives of its marginalised communities.

The Royal road

The monarchy exercises considerable influence over every major political decision, and this can have significant effect on the outcome of any vote. The constitution provides for the monarchy to remain an active political voice in governance, and in the appointment of parliamentarians to the upper house of parliament, security chiefs and constitutional office holders. The monarchy has also adopted a strategy to win the hearts of the general public, with King Khesar walking to villages in Bhutan’s remote districts in order to listen to the grievances of the people, help settle land ownership disputes and provide counsel in times of natural disaster – such as the 2009 earthquake in eastern Bhutan. He also reached the Haa and Wangdue Phodrang fire disasters faster than the local fire service.

Despite Bhutan’s move towards a democracy with a constitutional monarch, political actors are seeking a greater role for the monarchy. National Council members seek royal directives on whether they should resign in order to re-contest seats. MPs seek royal advice on whether certain parties should get state funding, and local government leaders supplant the national government, preferring instead to receive the king’s blessings for their plans. In some cases where Bhutan’s constitution has been called into question, politicians have approached the king for his interpretation, bypassing the Supreme Court. Moreover, political parties know that they must speak with affection and respect towards the monarchy in order to secure public support.

Thus, king indirectly reins on politics. Any political parties, not speaking in support of the monarchy will absolutely won’t win public sympathy. The mathematics of votes provides us sketch that victory in election could be of the party whichever appears to be closer to monarchy. Fragile hostility between palace with a section of people in east and south will have little impact to give victory to party without close relations with palace.

Conclusion

When vital factors of the democracy – political parties and election processes– are so weak, we cannot expect Bhutanese democracy to grow strong in short run. Weak presence of the political parties and election commission in public debate and activities to engage general people in democratic exercise will delay the process of strengthen democratic governance in Bhutan. To keep the legacy it received through promotion of GNH, Bhutan needs prudent and submissive leadership to ensure a vibrant and potent democratic culture.

Bhutanese democracy is rising above its myriad challenges. Changes are picking up gradually despite efforts by the ruling party and the palace to exert their control.

The leadership will be tested on how good and credible pro-people governing system they establish. Their fairness and robust calibre of giving a just democracy will be evaluated on how they examine and address the critical questions of Bhutanese political and social history.

Public criticism of government misdeeds and failures to deliver on commitments is starting to gain momentum. If political climate does not change swiftly in coming years, this dictated democracy will take years to mature. Bhutan must learn from regional experiences to let the system mature at the earliest possible and concretise stability to avoid instability and wobbly politics. We can’t expect greater political change in near future but cannot say no, again, for any abrupt outcomes from the century-long-suppressed society.

In any way, greater changes are obvious for this new democracy.

Keep on penning down your impure and dirty thoughts about Bhutan…………….